Benedetta, the biographical drama film about a 17th century lesbian nun who shakes the Church with her forbidden desires and religious visions, is – at its core – a good movie. The film is directed and co-written by taboo film-maker Paul Verhoeven and, predictably, is a little male-gazey when it comes to depicting lesbian intimacy. That is true. But the acting is incredible, the plot is suspenseful, and it left me thinking. That’s when I know a work of art is good.

Lesbianism and religion frequently go hand-in-hand in art. There’s Oranges Aren’t the Only Fruit (1985), a book by Jeanette Winterson. Then there’s films Disobedience (2017) and Novitiate (2017). They’re great. But when a man is making a film about lesbian nuns – double fetishization – and warns his actors there’ll be a lot of lesbian sex scenes – dildos included–you have a right to worry.

The good thing about Benedetta (Virginie Efira) is that the questionable lesbian sex scenes exist, but lesbian sex isn’t added for the sake of well-made pornography. The movie is moreso about trust, loyalty, corrupt institutions, and the mystic.

Who is she?

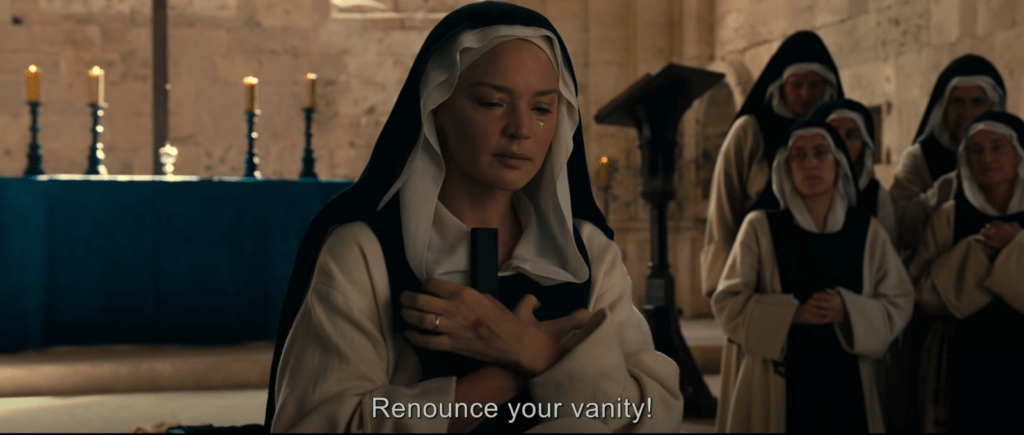

Benedetta entered the convent as a homesick child to a loving family who paid a lot of money for her place there. Immediately, a miracle happens. A statue of Mary falls on her without injury. Despite no reason for why she survived uninjured, some sisters secretly have doubts. Is it jealousy or reason?

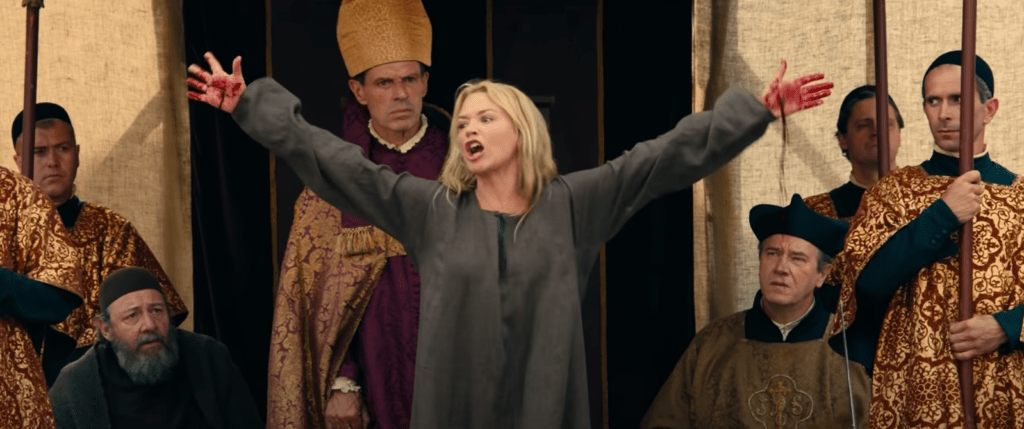

For the rest of the film, Benadetta believes she’s the true wife of Jesus and tries to convince the community so. Some believe her, some don’t. Weird events happen to her, like waking up with bleeding wounds in her palms and feet. She goes into fits of rage where her voice changes completely, becomes much more deep and menacing, and she speaks on behalf of Jesus. Some, including the priest, believe her. Others believe she’s putting it on. We never truly find out. It’s up to you.

Is love a miracle or temptation?

One of the people who aren’t completely sold–but never tell anybody–is her lover Bartolomea (Daphne Patakia). One morning, while Benedetta’s family is visiting, Bartolomea (a peasant) runs into the convent, distressed. She is followed by her violent father, who tries to remove her by force. Benedetta convinces her family to pay for Bartolomea’s entry and stay in the convent. They do.

Bartolomea and Benedetta are instantly attracted to each other but their courting is fit for the male gaze. There’s too much force, too much dominance/submission, it’s got the “rough is sexy” vibe that feels pornified. While Benedetta tries to avoid temptation, Bartolomea is a nature woman: she feels and acts on desire, and it’s not long before Benedetta can’t resist.

Their emotional connection is strengthened when Bartolomea confides in Benedetta that the bruises on her body are from her father, who “took her as his wife” when her mother died. The dynamic between Benedetta and Bartolomea is definitely reminiscent of Jesus and Mary Magdalen. The guilt for being lesbian doesn’t override the movie, which was surprising and relieving. The pair are quite confident in their love… for the most part.

Bartolomea trusts Benedetta, but not blindly. She’s a touch intimidated by the nun and, while Bartolomea loves her deeply, Benedetta doesn’t take criticism well. There’s always the risk she’ll “become Jesus” again and punish you for ill treatment of his wife. The way we get to see the inner mechanisms of Bartolomea’s mind, her suspicions without vocalization, is fantastic.

What are the suspicions?

The community questions Benedetta when she wakes with the holes in her hands and feet. The community questions where Jesus’ thorn marks on her head are. Miraculously, Mary’s statue falls on Benedetta again and she ends up with the thorn marks. When the statue’s lifted, Bartolomea (and another nun) see shards where she fell. Did she scratch herself?

Then there’s the end. The ex-head nun–replaced by Benedetta when people believe she’s miraculous–spies on Benedetta and Bartolomea while having sex with a hand-carved dildo made out of a mini Mary Benedetta had as a child, and travels to Florence to tell the Pope’s representative.

When the representative –who’s clearly a sexual pervert– comes to find evidence for the accusations that Benedetta is a liar and a lesbian, Benedetta and Bartolomea’s loyalty is tested. Bartolomea can only handle so much torture before she gives in, admits what they’ve done, which is motivated by a lack of faith in Benedetta and being triggered by sexualized punishments (trigger warning for sexual abuse in the punishment scene). Bartolomea immediately regrets the decision. Benedetta is betrayed.

When Benedetta is about to be burned but “turns into Jesus” again –riling up the peasants to fight the corrupt Church so she doesn’t have to die– Benedetta has holes in her hands again. That’s the proof the peasants need that she’s Godly. But when Bartolomea rushes to her aid, she finds a shard of statue in Benedetta’s hand. The shard could have been put there by God, to help Bartolomea undo the ropes Benedetta is tied up in. But it could also be proof that Benedetta cut her own palms.

Do you believe her?

I believe Benedetta. I think she’s a woman who’s really trying to convince people her visions and feelings are correct and right, even if they’re actually from madness. She might have cut the thorn marks into her own head when the Church questioned her -we don’t know- but that’s because they didn’t believe her when unexplainable things actually happened and demanded more proof.

I find it interesting that Benedetta refers to herself as Jesus’ wife, instead of Jesus himself. She’s much more powerful –like Jesus himself– than the powerless state a wife had to live in during that context. She “turns into Jesus” and “defends his wife” after she’s questioned for her visions, but then she returns to innocence. There’s a feminist reading in that.

It’s entirely possible that Benedetta’s strength doesn’t come from Jesus, but from herself. The statue could have resisted because of Benedetta’s super-human strength. The film is magic realism, although still biographical, so there’s every chance she has powers.

Overall, the film is about more than lesbianism. It’s about more than the Church. It’s about having conviction, being grounded in your beliefs, and surviving tests of loyalty. It’s about having unwavering faith in what you know is right, despite what your community thinks about you. It’s learning how to forgive people for being human, when they’ve deeply betrayed the love you share.

I think the film has a unique taste. I don’t think everyone who reads this will like it. But if you watch it closely until the end, you’ll at least have something to think about.